Want to Know What Emotional Incest Means? Here’s How

Emotional Incest Doesn’t Mean What You Think It Means: 3 Hard Truths

What “Emotional Incest” Really Means (And Why It Matters)

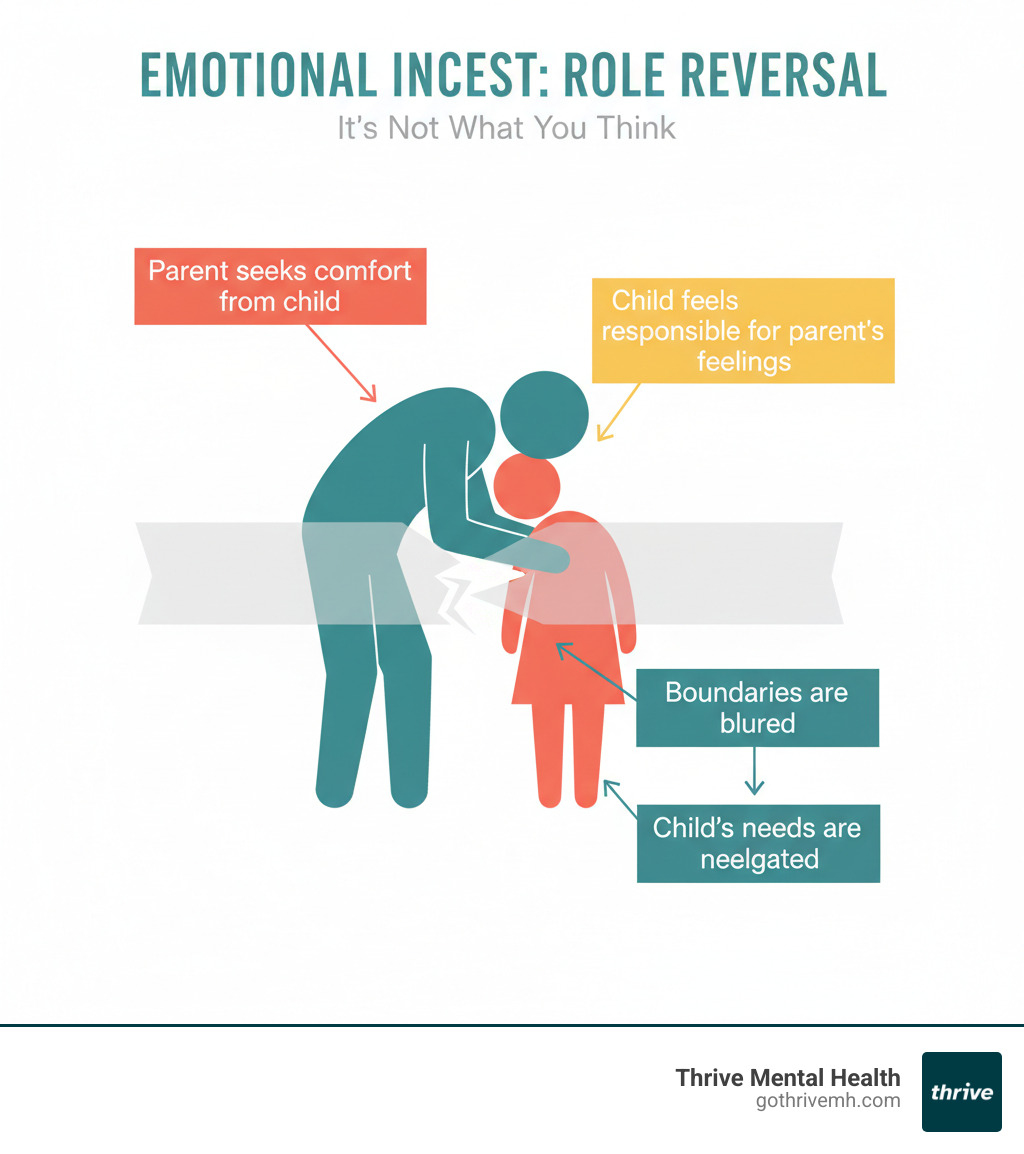

Emotional incest doesn’t mean what you think it means—despite the jarring name, it has nothing to do with sexual abuse. Instead, it describes a parent-child relationship where the parent leans on the child for emotional support that should come from an adult partner or peer. The child becomes a confidant, therapist, or surrogate spouse, forced into a role they’re not developmentally ready for.

Quick Answer: What Is Emotional Incest?

- Not sexual: No physical or sexual contact is involved.

- Role reversal: The parent treats the child like a partner or best friend.

- Emotional burden: The child is expected to meet the parent’s emotional needs.

- Blurred boundaries: Privacy, independence, and age-appropriate relationships are undermined.

- Long-term harm: Can lead to anxiety, codependency, relationship struggles, and identity issues in adulthood.

You might recognize this dynamic if you felt responsible for a parent’s happiness, were their go-to person for comfort after a fight, or felt guilty for having your own life. Maybe you dated someone who couldn’t set boundaries with their mom, or you’ve struggled with people-pleasing and not knowing what you actually want.

This pattern is more common than you’d think. Research shows that over 70% of adults have experienced some form of trauma, and emotional incest—also called covert incest or parentification—is one of the quieter, harder-to-name types. It doesn’t leave visible scars, but it shapes how you see yourself and relate to others for years.

The good news? Emotional incest doesn’t mean what you think it means when it comes to your future. Recognizing it is the first step toward healing, setting boundaries, and reclaiming your sense of self. You can break the cycle.

I’m Anna Green, LMHC, LPC, Chief Clinical Officer at Thrive Mental Health. I’ve spent my career helping people untangle complex relational trauma, including the lasting effects of emotional incest doesn’t mean what you think it means for many survivors. You’re not alone in this, and there’s a path forward.

If you’re in crisis, call or text 988 right now. You are not alone.

Simple Emotional Incest Doesn’t Mean What You Think It Means glossary:

Emotional Incest Doesn’t Mean What You Think It Means: A Clear Definition

Let’s get specific about what we’re actually talking about when we say “emotional incest.” This is a parent-child relationship where something fundamental gets flipped upside down: instead of the parent supporting the child emotionally, the child becomes the parent’s emotional caretaker, confidant, or even substitute partner.

It’s a role reversal that puts adult emotional weight on shoulders far too young to carry it.

The American Psychological Association defines covert incest as a form of emotional abuse, making it clear that this isn’t just an overly close relationship—it’s a dynamic where the adult prioritizes their own needs at the expense of the child’s mental well-being and healthy development.

You might hear this dynamic described in different ways, but they’re all pointing to the same problematic pattern. Parentification happens when a child takes on adult responsibilities, becoming the emotional caregiver for their parent—giving advice, mediating conflicts, providing comfort when the parent is upset. Enmeshment means boundaries between parent and child have dissolved; there’s an extreme closeness where neither person has room to be their own individual. The term surrogate spouse describes exactly what it sounds like: the child fills the emotional void left by a missing or unavailable adult partner, becoming the parent’s primary source of emotional support and intimacy.

The common thread? Blurred boundaries and a child who can’t just be a child. The parent shares inappropriate details about their romantic struggles, financial stress, or personal problems—treating their kid like a peer or therapist. Meanwhile, the child learns that their job is to manage their parent’s feelings rather than explore their own.

Here’s what makes this different from a healthy, close parent-child relationship: In a healthy bond, the parent is the secure base. They provide emotional support, guidance, and a safe space for the child to grow, make mistakes, and develop their own identity. The parent shares age-appropriate information and respects the child’s privacy and autonomy. Communication flows naturally, but the parent never forgets they’re the adult in the room.

| Feature | Healthy Emotional Closeness | Emotional Incest |

|---|---|---|

| Support | Parent provides emotional support and security to the child. | Child provides emotional support and comfort to the parent. |

| Boundaries | Clear, age-appropriate boundaries are maintained; child’s privacy and autonomy are respected. | Boundaries are blurred or non-existent; child’s privacy is often invaded. |

| Communication | Parent shares age-appropriate information; child feels safe to express themselves. | Parent overshares adult problems; child feels obligated to listen and advise. |

| Roles | Parent is the caregiver; child is nurtured and allowed to be a child. | Child assumes a partner or confidant role; parent relies on child for adult needs. |

| Purpose | Fosters child’s healthy development and independence. | Serves parent’s unmet emotional needs; hinders child’s development. |

What Causes This Unhealthy Dynamic?

Here’s something important to understand: most parents who create this dynamic aren’t doing it on purpose. They’re not sitting around plotting how to emotionally burden their kid. Instead, emotional incest doesn’t mean what you think it means in terms of intent—it usually comes from a parent’s own pain, loneliness, or lack of healthy coping tools.

Parental loneliness is a big one. After a divorce, the death of a spouse, or when a parent simply doesn’t have close friends, they might turn to their child to fill that empty space. It feels natural to them—this person they love and who loves them back—but it puts the child in an impossible position.

Marital problems create another pathway. When the relationship between parents is broken, cold, or filled with conflict, one parent might seek emotional intimacy from a child instead. The child becomes the person they confide in, lean on, share with—essentially becoming a partner without either of them naming it that way.

Many parents struggling with unresolved trauma from their own childhood simply don’t have a roadmap for healthy parenting. If they experienced emotional incest themselves or grew up with neglect, they might not recognize they’re repeating the pattern. They’re parenting from a place of their own unmet needs.

A lack of adult support plays a role too. When a parent doesn’t have friends, family members, or a partner they can turn to, that emotional pressure has to go somewhere—and sometimes it lands on the child who’s right there, loving and eager to help.

Sometimes narcissistic traits are part of the picture. Parents with these tendencies may view their children as extensions of themselves rather than separate people with their own needs. The child exists to validate the parent, boost their self-worth, and meet their emotional demands. If this resonates, you might find it helpful to read more on narcissistic parents.

Emotional Incest vs. Enmeshment

You’ve probably heard both terms, and yes, they’re related—but they’re not quite the same thing.

Enmeshment is the broader umbrella. It’s a family system where boundaries between any family members have become fuzzy or nonexistent. Individual identities get lost in the family unit. You see it between siblings, between parents, across generations—everyone’s overly involved in everyone else’s business, thoughts, and feelings. Nobody has space to be their own person.

Emotional incest is more specific. It’s a type of enmeshment that zeroes in on the parent-child relationship, with that particular role reversal where the parent treats the child as an emotional partner. The parent’s adult emotional needs—the kind that should be met by a spouse, partner, or adult friend—get placed on the child instead.

Think of it this way: all emotional incest involves enmeshment, but not all enmeshment is emotional incest. The key is whether a child is being pulled into an adult emotional role they’re not developmentally ready for.

Understanding the difference matters because it helps you name what happened and find the right path forward for healing.

Recognizing the Signs of Emotional Incest

Identifying emotional incest can feel like trying to see through fog. It’s often wrapped in what looks like love, closeness, or just “being there” for a parent who needs you. The “covert” part of covert incest means exactly that—this type of emotional abuse hides in plain sight, disguised as devotion or family loyalty. Even the people living through it often can’t name what feels so wrong.

Emotional incest doesn’t mean what you think it means when you’re in the middle of it. You might have grown up thinking it was normal to be your mom’s best friend, or that all kids feel responsible when their dad is sad. It’s only later, when you notice patterns in your own relationships or feel that constant weight of guilt, that the pieces start to come together.

There are common threads that run through these experiences. Guilt is often the loudest—a crushing feeling that you’re letting your parent down if you don’t answer their late-night calls, if you move away, or if you dare to have your own life. This guilt doesn’t come from nowhere; it was carefully cultivated over years of being told, directly or indirectly, that your parent’s emotional well-being depends on you.

Jealousy from the parent is another red flag. They might act hurt or angry when you spend time with friends, start dating, or get excited about your own goals. Your independence feels like betrayal to them, so they pull you back in—sometimes with tears, sometimes with anger, sometimes with just enough neediness to make you cancel your plans.

Lack of privacy was probably your normal. Maybe your parent read your diary, listened in on phone calls, or expected you to share every detail of your day and inner thoughts. The idea that you could have something just for yourself—a boundary, a secret, even just space to think—felt foreign or forbidden.

And then there’s people-pleasing. You learned early that your value came from meeting others’ emotional needs, from being the “good” kid who always knew what to say to make things better. This pattern doesn’t just disappear when you turn 18. It follows you into friendships, romantic relationships, and work environments, where you automatically prioritize everyone else’s comfort over your own needs. This is often called a fawning response—a trauma reaction where you instinctively try to keep others happy to feel safe. You can learn more about understanding the fawning response.

Signs in Childhood and Adolescence

Looking back at your childhood, certain patterns might stand out now that didn’t seem strange at the time.

You probably felt overly mature for your age. While other kids were playing or worrying about homework, you were thinking about whether your mom was okay after another fight with your dad. People might have praised you for being “so mature” or “an old soul,” but what they didn’t see was that you didn’t get a choice. You had to grow up fast because someone needed to be the adult.

Mediating parental arguments might have been your unofficial job. You stood between your parents during fights, tried to calm everyone down, or felt responsible for keeping the peace. No child should be a marriage counselor, but you were expected to steer adult conflicts and somehow fix what was broken between them.

Being the parent’s primary confidant meant hearing things no kid should hear. Details about their romantic life, complaints about your other parent, financial stress, or personal struggles that left you feeling confused and burdened. You became the keeper of secrets, the shoulder to cry on, the one who had to have all the answers.

You might have given up activities you loved—sports, friends, hobbies—because your parent needed you home. Maybe they made you feel guilty for wanting to go out, or they scheduled their emotional crises right when you had plans. Over time, you learned to just stay home, to be available, to put their needs first.

And underneath it all was the crushing weight of feeling responsible for their happiness. If your parent was sad, you felt like you’d failed. If they were angry, you scrambled to fix it. Their emotional state became your report card, and you never quite felt like you were doing enough.

Signs in Adulthood

The effects don’t stay in childhood. They show up in your adult life in ways that can feel confusing or frustrating, especially when you can’t figure out why certain patterns keep repeating.

Difficulty setting boundaries is often the most visible struggle. You might know intellectually that you should be able to say no, to have limits, to prioritize your own needs—but actually doing it feels impossible. The guilt kicks in immediately, and you find yourself backing down, over-explaining, or just giving in to keep the peace.

Fear of abandonment can drive your relationships. You might panic when someone doesn’t text back quickly, assume people will leave you if you’re not perfect, or stay in unhealthy relationships because being alone feels terrifying. This fear was learned early, when your parent’s love felt conditional on you meeting their needs.

You might notice yourself choosing emotionally unavailable partners again and again. On some level, the dynamic feels familiar—you’re trying to earn love, to fix someone, to be enough. It’s the same role you played with your parent, just with a different person.

Low self-esteem often runs deep, even when you look successful on the outside. You might accomplish a lot but never feel like you’re truly good enough. Your worth still feels tied to what you can do for others, not who you are as a person.

Chronic guilt is your constant companion. You feel guilty for resting, for having fun, for putting yourself first in any way. You feel guilty when you don’t answer your parent’s calls immediately, when you set a boundary, or when you dare to be happy while they’re struggling.

And that pattern of people-pleasing or fawning continues. You automatically say yes when you want to say no. You read every room, adjust your personality to make others comfortable, and exhaust yourself trying to keep everyone happy—except yourself.

If you’re reading this and seeing yourself in these patterns, you’re not alone. At Thrive Mental Health, we work with adults who are untangling these complex dynamics and learning to reclaim their own lives. Our personalized therapy for teens and adult programs can help you understand these patterns and develop healthier ways of relating to yourself and others.

The Lasting Scars: How Emotional Incest Affects Your Adult Life

The wounds from emotional incest don’t heal just because you’ve grown up and moved out. In fact, many people don’t even realize they’re carrying these scars until they’re in their twenties, thirties, or even later—when patterns in their relationships and inner life start feeling painfully familiar.

Here’s the thing: when you spend your childhood being the emotional caretaker for a parent, you miss out on something fundamental—the chance to figure out who you are. Your emotional energy, which should have been spent exploring your own interests, making mistakes, and learning what you like and don’t like, was instead constantly directed toward managing someone else’s feelings. That doesn’t just disappear when you turn eighteen.

The psychological impact shows up in ways that can feel confusing or even contradictory. Anxiety becomes a constant companion—that nagging sense of unease, the overthinking, the worry that you’re not doing enough or being enough for the people around you. You might find yourself constantly scanning for signs that someone’s upset with you, just like you used to watch your parent’s moods.

Depression can settle in too, often rooted in a deep sense that your own needs don’t really matter. When you’ve spent years pushing down your feelings to make room for someone else’s, it’s hard to access joy or motivation. There’s a heaviness that comes from never having been allowed to just be a kid.

Many survivors develop what therapists call codependency—a pattern where you derive your sense of worth entirely from taking care of others. Your value feels tied to how much you can do for people, how well you can anticipate their needs, how successfully you can keep them happy. The thought of prioritizing yourself feels selfish, even dangerous.

Perhaps most painfully, you might struggle with identity issues—not knowing who you are when you’re not performing a role for someone else. What do you actually like? What do you want? These questions can feel impossibly hard to answer because you never got the space to explore them.

Research backs up what survivors instinctively know. The Childhood Emotional Incest Scale (CEIS) links it to lower life satisfaction and increased anxiety in adulthood. This validated assessment tool measures experiences like being expected to show more maturity than your parents or being asked to advise them on their romantic problems. The findings are clear: these childhood dynamics have measurable, lasting effects on adult well-being. It’s part of the impact of trauma on daily life that many people carry without fully understanding where it came from.

Long-Term Impacts: Emotional Incest Doesn’t Mean What You Think It Means for Your Future

The good news—and yes, there is good news—is that Emotional Incest Doesn’t Mean What You Think It Means when it comes to your future. These patterns aren’t permanent. They’re learned, which means they can be unlearned. But first, it helps to understand how they’re showing up in your adult life.

Romantic relationships often become a minefield. You might find yourself repeatedly drawn to partners who are emotionally unavailable or who need “fixing,” unconsciously recreating that familiar dynamic where you’re the caregiver. Or you might swing the other direction, choosing partners who are overly dependent, because at least then you know your role. True intimacy—where both people are equals, where you can be vulnerable without being responsible for the other person’s emotional stability—can feel foreign, even threatening.

Your ability to trust has likely taken a hit. When the person who was supposed to protect your boundaries was the one violating them, when the relationship that should have felt safest was the one that demanded too much, it makes sense that you’d approach relationships with caution. You might find yourself holding back, waiting for the other shoe to drop, or conversely, oversharing too quickly in an attempt to create false intimacy.

Many survivors develop what attachment researchers call an anxious attachment style. This shows up as constantly seeking reassurance from partners, feeling panicked when they pull away even slightly, and struggling with a stable sense of self within relationships. You might feel like you’re “too much” or “too needy,” but really, you’re just trying to get needs met that should have been met decades ago.

The risk for Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD) is significantly higher among those who experienced emotional incest, especially when combined with other forms of neglect or emotional abuse. C-PTSD involves ongoing difficulties with regulating emotions, a deeply negative self-perception, chronic relationship problems, and sometimes a sense that life has lost its meaning. It’s the result of prolonged, repeated trauma during developmental years.

Perhaps the most persistent struggle is difficulty recognizing your own needs. After a lifetime of prioritizing someone else’s emotional well-being, your own needs can feel like background noise—or completely silent. You might not even notice you’re hungry, tired, or upset until your body forces you to pay attention. Learning to tune into yourself, to ask “What do I need right now?” without immediately dismissing the answer, is a skill that many survivors have to consciously rebuild.

Is It a Form of Child Abuse?

Let’s be direct: yes, emotional incest is child abuse. Full stop.

This can be hard to accept, especially if your parent “meant well” or if you have positive memories alongside the painful ones. But emotional abuse doesn’t require malicious intent to cause real harm. The American Psychological Association defines covert incest as a form of emotional abuse, specifically noting that the adult prioritizes their needs over the child’s at the expense of the child’s mental well-being.

It’s also a form of emotional neglect. While it might look like intense closeness from the outside, the child’s actual needs—for security, for age-appropriate boundaries, for the freedom to develop their own identity—are being profoundly neglected. The attention you received wasn’t about nurturing you; it was about using you to meet adult needs.

The psychological harm is real and measurable. Children need their primary caregiver to be a source of safety and security, not a source of emotional demands. When you’re put in charge of a parent’s emotional stability, it creates deep insecurity and disrupts your ability to individuate—to develop a separate sense of self. This developmental disruption has ripple effects throughout your entire life.

There’s strong expert consensus on this point. Licensed therapists, including marriage and family therapist Kathy Hardie-Williams, state clearly that emotional incest is child abuse, even when it’s unintentional. The parent’s lack of awareness or intent doesn’t erase the impact on the child.

While emotional incest isn’t prosecuted in the same way physical or sexual abuse is, recognizing it as abuse is crucial for your healing. It validates your experience, explains your struggles, and opens the door to appropriate treatment. You didn’t cause this, and you’re not overreacting by acknowledging the harm it caused.

Your Path to Healing: How to Recover and Break the Cycle

Recognizing that you’ve experienced emotional incest is one of the bravest things you’ll ever do. It takes courage to see a painful pattern for what it is, especially when it involves someone you love. But this recognition—this moment of clarity—is also the foundation for everything that comes next. Emotional incest doesn’t mean what you think it means has to define the rest of your life. Healing is possible, and it starts right here.

The path forward isn’t always linear. There will be moments of grief, frustration, and even guilt—especially as you begin to set boundaries or pull back from familiar patterns. But there will also be moments of profound relief, self-findy, and freedom. You’re not just recovering from something; you’re actively building a new relationship with yourself.

Acknowledging the dynamic is the essential first step. This means accepting that what you experienced wasn’t typical, even if your parent didn’t intend harm. It means validating your own feelings—the confusion, the resentment, the sadness—and understanding that you deserved better. Many people struggle with this step because they love their parent or because the parent was suffering too. But acknowledging the truth doesn’t mean you’re being disloyal. It means you’re finally being honest with yourself.

Once you’ve acknowledged what happened, you’ll likely need to grieve the lost childhood. This grief is real and valid. You might mourn the carefree years you didn’t have, the innocence that was taken too soon, or the parent-child relationship you deserved but never received. Allow yourself to feel this loss. Cry if you need to. Talk about it. Write about it. Grieving isn’t weakness—it’s how we process pain and make space for healing.

Throughout this process, self-compassion is your greatest ally. You might catch yourself thinking, “I should have known better” or “I’m too sensitive.” Stop. Reframe those thoughts. The coping mechanisms you developed—people-pleasing, difficulty saying no, avoiding conflict—weren’t character flaws. They were survival strategies. You did what you had to do to stay emotionally safe in an unsafe situation. Now you’re learning new, healthier ways to steer the world, and that takes time.

Perhaps the most challenging but transformative work involves setting firm boundaries. This might mean telling your parent you can’t be their therapist anymore. It might mean limiting phone calls, declining invitations, or refusing to engage in certain conversations. Boundaries aren’t about punishing anyone—they’re about protecting your emotional space and reclaiming your autonomy. They will likely feel uncomfortable at first, especially if you’re met with guilt-tripping or resistance. But boundaries are how you teach people how to treat you, and they’re non-negotiable for your well-being.

The Role of Professional Therapy

While self-help strategies are valuable, working with a therapist who understands trauma can accelerate your healing in profound ways. A good therapist provides a safe, non-judgmental space where you can finally put your own needs first—maybe for the first time in your life.

Trauma-informed care is especially important for emotional incest survivors. Therapists trained in approaches like Internal Family Systems (IFS) can help you identify and heal the different parts of yourself that developed in response to the trauma. Somatic therapy addresses the ways trauma gets stored in your body—the chronic tension, the hypervigilance, the physical manifestations of anxiety. These modalities recognize that emotional incest isn’t just a mental health issue; it affects your entire being.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is another powerful tool. It helps you identify the distorted thought patterns that may have taken root during childhood—beliefs like “I’m only valuable if I’m helping others” or “My needs don’t matter.” CBT gives you practical strategies to challenge and reframe these thoughts, replacing them with healthier, more balanced perspectives.

In some cases, family therapy can be beneficial, but only if the parent is genuinely willing to acknowledge the dynamic and do their own work. Family therapy can educate parents about healthy boundaries, facilitate difficult conversations, and help repair the relationship on more equitable terms. However, if the parent is defensive, dismissive, or unwilling to change, family therapy may not be appropriate or safe for you.

One of the most important gifts therapy offers is the opportunity to rebuild your self-identity. Who are you when you’re not constantly managing someone else’s emotions? What do you actually want? What are your values, separate from what you were taught? These questions might feel overwhelming at first, but exploring them is how you reclaim your sense of self. For more information on different therapeutic approaches that might resonate with you, visit a guide to different therapy types.

Steps to Heal When Emotional Incest Doesn’t Mean What You Think It Means Anymore

Beyond therapy, there are several practices you can integrate into your daily life that support healing and self-findy.

Journaling creates a private space where you can be completely honest about your thoughts and feelings without fear of judgment or consequences. Write about your childhood memories, your current struggles, or what you hope for your future. Over time, you’ll likely notice patterns, gain insights, and experience the relief that comes from simply naming what you’ve been through.

Mindfulness practices—like meditation, deep breathing, or even mindful walking—help you stay grounded in the present moment. When you’ve spent years hypervigilant to someone else’s emotional state, mindfulness teaches you to tune into your own body and emotions. It’s a way of coming home to yourself.

Building a healthy support system is crucial. Surround yourself with people who respect your boundaries, celebrate your growth, and don’t expect you to be their emotional caretaker. This might include friends, chosen family, support groups, or mentors. Look for relationships that feel reciprocal and nourishing, not draining.

Prioritizing self-care isn’t selfish—it’s essential. This means engaging in activities that genuinely restore you, whether that’s reading, exercising, creating art, spending time in nature, or simply resting. Self-care is about learning to value your own well-being as much as you’ve valued others’.

Finally, learning to re-parent yourself is a powerful practice. This means giving yourself the nurturing, validation, and structure you may have missed growing up. When you’re scared, comfort yourself. When you accomplish something, celebrate. When you need rest, allow it. You’re essentially becoming the parent to yourself that you deserved all along.

Accessing Care: Insurance and Program Options

Finding the right professional support can feel overwhelming, but you don’t have to steer it alone. At Thrive Mental Health, we specialize in helping adults and young professionals heal from complex relational trauma, including the lasting effects of emotional incest. Our intensive outpatient (IOP) and partial hospitalization (PHP) programs offer comprehensive, evidence-based care that fits into your life.

We understand that you’re busy, which is why we offer virtual and in-person options with evening availability. Whether you’re in Indiana, California, Florida, Arizona, or South Carolina, you can access expert-led treatment from wherever feels most comfortable. Our approach is flexible and custom to your unique needs—because your healing journey is yours alone.

We also work with major insurance providers, including Cigna, Optum, and Florida Blue, to make quality mental health care accessible and affordable. You can verify your insurance coverage in just two minutes with no obligation. Our team is here to help you understand your benefits and remove any barriers to getting the support you deserve.

Frequently Asked Questions about Emotional Incest

Understanding emotional incest doesn’t mean what you think it means can bring up a lot of questions. Here are some of the most common ones we hear, answered with care and clarity.

Is emotional incest always intentional?

No, and this is one of the most important things to understand. Most parents who engage in covert incest aren’t deliberately trying to harm their children. They’re often acting from their own unresolved trauma, deep loneliness, or a complete lack of healthy adult support. Many genuinely don’t see their approach to parenting as problematic—they might even believe they’re building a “special bond” or being a “close” family.

That said, the lack of intent does not erase the harm caused to the child. Just as accidentally stepping on someone’s foot still hurts them, unintentionally leaning on your child for adult emotional needs still causes real, lasting damage. The impact on the child’s development, self-esteem, and future relationships is the same whether the parent meant to cause harm or not. Recognizing this can be freeing—it allows you to validate your own pain without needing to villainize your parent.

What is the difference between a close parent-child bond and emotional incest?

This is a crucial distinction, because emotional incest often masquerades as closeness or love. A healthy, close parent-child bond is reciprocal and age-appropriate. The parent provides a secure base—offering guidance, comfort, and support—while actively encouraging the child’s independence and individual identity. The child feels safe to explore, make mistakes, and develop their own thoughts and feelings. The relationship serves the child’s developmental needs.

Emotional incest, however, involves a role reversal. The parent relies on the child to meet their adult emotional needs—needs that should be fulfilled by a partner, therapist, or adult friends. The parent might share intimate details about their romantic life, financial stress, or personal struggles. They might become jealous of the child’s other relationships or guilt-trip the child for wanting independence. The relationship crosses boundaries and hinders the child’s ability to form their own identity and healthy relationships outside the family.

The key question to ask yourself: Does this relationship primarily serve the child’s growth and well-being, or is it filling the parent’s emotional gaps? If it’s the latter, you’re likely looking at emotional incest, not just closeness.

Can you heal from emotional incest while still in a relationship with the parent?

Yes, healing is possible while maintaining contact with your parent, but it’s challenging and requires immense courage and commitment. It’s not the easier path, but for many people, it’s the one they choose—and that’s valid.

The cornerstone of healing while staying in relationship is establishing and consistently enforcing strong boundaries. This means clearly defining what you will and won’t discuss, how much time you’ll spend together, and what behaviors you’ll no longer tolerate. It might sound like, “I’m not comfortable talking about your relationship with Dad anymore,” or “I need you to call before dropping by.” Expect pushback. Your parent may feel hurt, confused, or even angry when you start setting limits.

Therapy is crucial to guide this process. A skilled therapist can help you steer the guilt (because you will feel guilty), practice boundary-setting in a safe space, and build a strong sense of self separate from your parent’s needs and expectations. They can also help you determine if the relationship is truly salvageable or if limited contact—or even no contact—might be necessary for your well-being.

Some relationships can evolve into healthier dynamics with work, especially if the parent is willing to acknowledge the past and make changes. Others cannot. There’s no shame in whatever choice protects your mental health.

Take the First Step Toward Healing

You’ve made it this far, and that matters. Emotional incest doesn’t mean what you think it means when you first hear the term—it’s not about physical violation, but about the invisible weight of emotional burdens you carried far too young. The impact is real, the confusion is valid, and the pain you’ve felt doesn’t need justification.

Recognizing this pattern in your life takes courage. Maybe you’re reading this and finally have words for something that’s felt wrong for years. Maybe you’re realizing why relationships feel so complicated, or why setting boundaries makes you feel like you’re betraying someone. This awareness? It’s not the end of something—it’s the beginning of reclaiming yourself.

Healing from emotional incest involves understanding how it shaped you, grieving the childhood that prioritized someone else’s needs over yours, and learning that your worth isn’t measured by how well you care for others. It means setting boundaries that might feel uncomfortable at first, but protect the person you’re becoming. It means rebuilding your sense of self—finding what you want, what you feel, and who you are when you’re not performing a role.

You don’t have to steer this alone. Professional support can make all the difference, helping you untangle years of conditioning and build healthier patterns. At Thrive Mental Health, we understand the complexity of relational trauma. Our virtual and hybrid IOP and PHP programs offer flexible, evidence-based care with evening options, so you can access support from anywhere in Indiana, California, Florida, Arizona, or South Carolina.

Ready to start? Verify your insurance in 2 minutes with no obligation—we work with providers like Cigna, Optum, and Florida Blue to make care accessible. Call us at 561-203-6085, or begin your journey toward healing today.

If you’re in crisis right now, call or text 988. You deserve support, and help is available immediately.